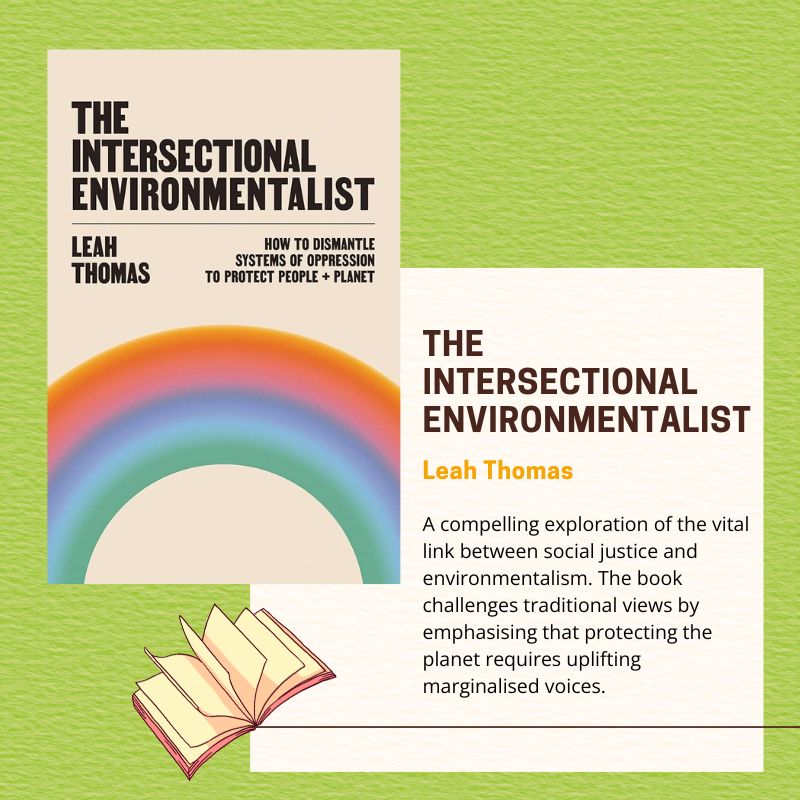

To care about the planet, is to care about all its inhabitants, especially those who are worst affected. This is the point that Leah Thomas tries to make in her book The Intersectional Environmentalist as she says, ‘The future can and will be intersectional’. It is our ‘Climate Currents’ recommendation for October.

Leah Thomas’s book The Intersectional Environmentalist, is an introduction to the intertwined nature of environmentalism, racism, and privilege. By coining the term ‘Intersectional Environmentalism’ (IE), Thomas emphasises that caring for the planet inherently involves caring for its people. This foundational idea resonates throughout the book: one cannot exist without the other. The narrative challenges traditional environmentalism, which often overlooks human impact, urging readers to recognise that humans are integral to the ecosystem.

Thomas asserts, ‘We should care about the protection of people as much as we care about the planet,’ highlighting that these fights are interconnected. For instance, she discusses lithium mining in South America, where a significant portion of the world’s lithium resides on Indigenous lands. The mining operations deplete local water sources and fail to adequately compensate Indigenous communities, raising questions about the ethical implications of green technologies. This is one of many examples that illustrates how environmental issues often intersect with social justice, reinforcing the book’s core message.

While The Intersectional Environmentalist presents a compelling argument for integrating social justice into environmental activism, it does have a noticeable US-centric focus. Thomas primarily addresses issues relevant to American audiences, which may limit its applicability in a global context. However, Thomas’s approach remains accessible and engaging, making complex topics digestible for a younger audience or those new to these discussions.

The importance of this book lies not only in its exploration of race but also in its comprehensive coverage of related topics. Thomas addresses privilege directly, guiding readers through recognizing their own advantages and understanding how they can leverage this awareness for advocacy. She writes, ‘Recognising privilege isn’t meant to shame you… it’s what you do with it that matters.’ This approach fosters empathy and encourages actionable steps toward equity.

Though the primary focus of the book is race, ‘The Intersectional Environmentalist’ extends its analysis to other areas of vulnerability related to climate justice. The way Thomas dissects the relationship between race, privilege and environmentalism, can effectively serve a roadmap for understanding how various forms of oppression intersect and impact marginalized communities in unique ways.

The book also includes discussion questions along with lists of recommended readings, videos, and podcasts at the end of each chapter, making it a valuable tool for group or classroom settings. These prompts encourage readers to reflect on their own experiences and engage in meaningful conversations about climate justice and social equity. This dual function—serving as both a casual read and a discussion starter—makes the book suitable for a large audience.

Though lacking in depth in certain sections, Thomas’s engaging writing style and thoughtful insights make the book an essential read for anyone interested in merging social justice with environmentalism.

Whether you are new to these concepts or seeking to deepen your understanding, this book offers essential insights into the complexities of intersectionality within environmentalism. It serves as both a call to action and a guide for those eager to engage thoughtfully with pressing global issues that are ‘Inseparable, intertwined, and intersectional’.