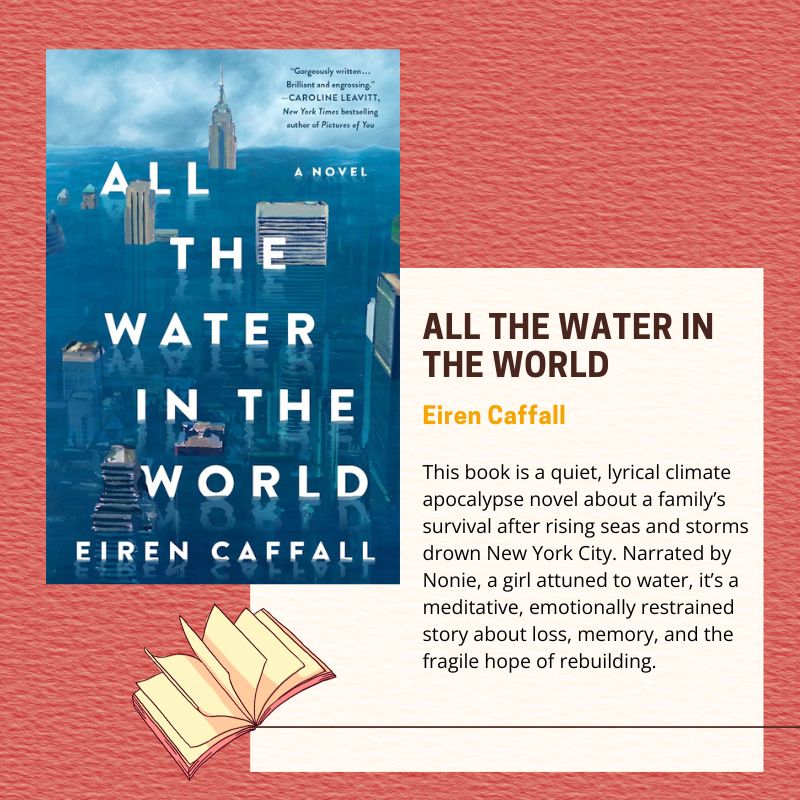

Eiren Caffall’s All the Water in the World is a haunting, almost lyrical tale of survival in a post-climate collapse world. Told through the voice of Nonie, a young girl with a mystical sensitivity to water, the story unfolds in the hushed ruins of a drowned New York City. As her family shelters atop the American Museum of Natural History, trying to preserve human history amid rising seas, we’re drawn into a vision of a world undone by climate change and yet stubbornly clinging to fragments of humanity, memory, and hope.

Caffall’s premise is striking: the glaciers have melted, sea levels have swallowed cities, and violent hypercanes now batter what’s left. Nonie’s family – her older sister Bix, their scientist parents, and a few close allies – are among the last holdouts in Manhattan. But when a monstrous storm breaches the flood walls, they’re forced to flee up the Hudson in a birch bark canoe, carrying with them a book recording what’s been lost — an archive of memory and history.

The writing is often poetic, interspersed with vivid memories and meditations on water, loss, and resilience. The apocalypse in All the Water in the World isn’t loud or flashy – it’s deeply personal. There are no zombies or aliens, just the brutal consequences of ecological neglect, and the quiet bravery of people trying to live through it. Some words, some sentence, some pages feel almost too real, too plausible. The novel captures our current fears; storm seasons out of sync, tropical heat in November, polar cold in the South, and projects them just a bit further into a future that feels chillingly plausible.

Yet, this book will not work for everyone.

For some it may feel too subdued. Nonie’s voice, while unique, is not emotionally expressive in a conventional sense. She often seems detached, which can make it hard to fully invest in her experience. This may be intentional. There’s a strong case to be made that Nonie is neurodivergent, possibly autistic, as she struggles with social cues, emotional expression, and even speech during stress.

Another point of division is the pacing. The novel is slow. This also feels deliberate. It lingers in quiet moments, lets scenes breathe, and relies on atmospheric dread more than plot twists. There’s definitely action – the escape from New York, encounters with dangerous communities on the river, the constant threat of storms – but it’s not action-packed. Instead, the novel balances survival horror with a quiet elegy for a world already lost.

Thematically, All the Water in the World is dense with grief, but not without light. The characters, especially Nonie and Bix, evolve under pressure. There’s violence and lawlessness, yes, but also resistance, compassion, and a search for a new ethical way of living. Found family, art, nature, and memory become essential lifelines. The book asks: What do we save when everything’s gone? And what does it mean to build a future, not just endure the present?

While the ending is void of a neat resolution, it offers hope, something believable and necessary. The survivors push forward, not out of blind optimism but out of love for what was and what might still be. That tone makes All the Water in the World feel less like standard apocalyptic fare and more like a eulogy turned survival manual. Stark, sad, and fiercely alive.

If you’re drawn to quiet apocalypse stories with lyrical prose, a strong sense of place, and thoughtful character work, this is a powerful, timely read. It’s less The Hunger Games and more Station Eleven by way of The Road, with a little magical realism thrown in.

It’s not an easy read. Slow, sad, often heavy, but it’s a resonant one. It raises difficult questions and doesn’t pretend to have easy answers. In a time where climate collapse feels less like fiction and more like forecast, that might be exactly the kind of story we need.